I am always interested in how people cope with a difficult

situation, and especially how they make the most of it. Take, for instance, the

reactions of the men of Stalag Luft III to their new environment.

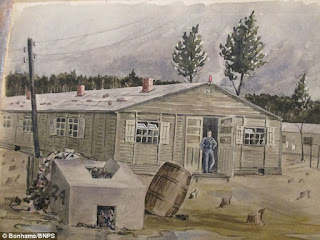

Stalag Luft III, in 1945, sketched by James R Taylor. Jim Taylor, a Scot, had given the original of this pencil drawing to Ken Carson. Courtesy of John Carson.

Each compound was ringed by

two barbed wire fences, 10 feet high, whose tops sloped inwards, making

climbing difficult. The 6 feet gap between—the Löwengang, or Lions Walk—was filled with thick coils of barbed

wire, about 3 feet high. (The Vorlarger

was also enclosed by a barbed wire fence.) Thirty or so feet from the inside

barbed wire fence, 18 inches from the ground, was a warning line ‘beyond

which’, Justin O’Byrne recalled, ‘it was suicide to step’. But not immediately.

Prisoners were forbidden to

cross it but, if they did, they were given two alerts, after which the guards

were ordered to shoot. With so much barbed wire about, O’Byrne,

looking back on his wartime accommodation, likened it to ‘the usual type of

German concentration camp’.

Justin O'Byrne prior to his arrival at Stalag Luft III. Courtesy of Anne O'Byrne.

While those of Stalag Luft III’s complement with

experience in Buchenwald Concentration camp would perhaps disagree, the barbed

wire certainly did nothing for some prisoners’ well-being. As one man put it, ‘It is really a

horrible prospect looking out on a world through barbed wire: it gives you the

feeling of having absolutely nothing to do with it’. Others, however, took a

different view.

One

man told his correspondent that ‘if it were not for the barbed wire and sentry

boxes one could almost visualise a huge holiday camp’. Rather than gazing at

his new abode through rose-tinted glasses, this chap appears to have sanitised

his account for the benefit of the homefolks. He was not the only one to liken

Stalag Luft III to holiday accommodation. Peter Kingsford-Smith took up the

theme in his wartime log book. His drawing of the tree and barbed wire bordered

compound, with guard tower to the left and wooden hut to the right, took the

guise of a naïve travel poster captioned ‘furnish flats at mod[erate] rates.

Holidays-at-Sagan’. Promoting ‘summer & winter sports’ interested holiday

makers were to apply to ‘Luftwaffe headquarters’ or Stalag Luft 3’. Arthur

Schrock, also painted a mock travel poster, complete with pines, snow and

barbed wire, in his wartime log book entreating tourists to ‘Visit Sagan. A

Haven of Tranquility [sic] Midst the Pines of Nieder Schlesien [Lower Silesia]’.

Courtesy of Andrew RB Simpson.

Bill Fordyce depicted the ‘horrid result of life of debauchery &

drunken-ness at the “haven-in-the-pines” Stalag Luft 3’.

Courtesy of Lily Fordyce.

John Cordwell, much

taken with the coniferous tree-scape, captioned his depiction of North Compound

and its needle-y border ‘Heaven in the Pines!’; it was one of the few artefacts

Kenneth ‘Ken’ Carson brought out of the camp.

Ken Carson's copy of John Cordwell's map of North Compound. Courtesy of John Carson.

British-born Archibald Sulston’s

watercolour of a pine forest-backed hut in Peter Kingsford-Smith’s wartime log

book is also entitled ‘Heaven in the Pines!’ but his tongue, like the tongues

of the other artist-commentators, was firmly planted in cheek given the presence

of an overflowing waste container, large puddles of water, an unsteadily-leaning

wooden cask and a number of tree stumps in the drawing’s foreground. (It seems

as if this was a common theme for Sulston because he painted a similar image in

his own log book.)

Archibald Sulton's rendition in his own log book. Lifted, with thanks, from http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3058534/Enola-Gay-pilots-flight-logs-Hiroshima-plans-sale.html.

For

some, there was no humour in the depiction of the camp as haven or heaven. Jock Bryce thought one of the Red Cross magazines erred ‘on the bright

side when it described Luft III as “the heaven in the pines”’. John

Osborne may have ‘almost settled down’ after his

recent arrival, but was quick to tell his family that ‘it’s no heaven’. Osborne

also resented the rosy portrayal of the camp by the Red Cross who frequently

reprinted extracts from letters, such as the barbed-wire holiday camp mentioned

above, depicting the brighter side of life. ‘What tales do the Red Cross print

of our conditions?’ Albert Hake, however, was more than content with the images

of ‘the

pleasant pictures of happy POWs which I am assured are portrayed to worried

relatives’ by the Red Cross and Prisoners of War Relatives’ Association. It

gave him comfort knowing that his wife Noela was taken in by them.

At least one

man categorically believed that Stalag Luft III was both haven and as close to

paradise as you could get in a prisoner of war camp. ‘After two months of hell

of earth’ at Buchenwald Concentration Camp, where every hair on Keith Mill’s

body had been shaved off, and he and his fellow prisoners, including eight

other Australian airmen had ‘slept with rocks for our beds and the sky for our

blanket for three weeks’ before managing ‘at last to get into a hut about 50

yards long with 700 people in it’ where they saw people die there, ‘some in

strange ways’, Stalag Luft III ‘was heaven’.

Keith Mills and his wife, Val, in 2004. Lifted, with thanks, from http://www.dailymercury.com.au/news/true-gentleman-bows-out/1280342/ (Read this touching obituary.)