Jimmy

Catanach had been a prisoner of war for almost seven months before unburdening

himself to his brother, Bill, on 28 March 1943. It had been a long journey from

Melbourne, where he had been born on 23 November 1921, to Stalag Luft III, Sagan. He had enlisted in the RAAF

when he was 18; was promoted to squadron leader; and had been awarded

a Distinguished Flying Cross for daring raids over Lorient in north-western

France, and the German cities of Cologne, Hamburg, Essen, and Lubeck, all before his 21st birthday.

The most recent stage of his journey to captivity had begun on 4 September 1942.

Numbers 144 and 455

squadrons had been deployed to Russia as part of Operation Orator, to protect a convoy taking vital supplies to Russia: Jimmy

was 455 Squadron’s youngest squadron leader and was lauded as the youngest in

the RAAF. He was a lively, boisterous man, much loved by his crew and squadron

friends. His commanding officer, Grant Lindeman, recalled that, as they were

lined up to depart, ‘Jimmy of course couldn’t restrain himself to wait his turn; he taxied

into the first gap in the line and was off like a blooming rocket’. Lindeman

had ‘never seen such a wealth of superfluous energy in any individual over the

age of twelve as Jimmy constantly had at his disposal. He didn’t drink or

smoke; he talked at an incredible speed; he couldn’t stand still for a second,

but he hopped about all the time you were talking to him till you were nearly

giddy’. In his opinion, Jimmy ‘was a most excellent Flight Commander, and was

probably the most generally liked man in the whole squadron’.

Members of 455 Squadron, August 1942.

L-R: Jack Davenport, Jimmy Catanach, Grant Lindeman, Les Oliver, Bob Holmes. Author's collection

Jimmy was piloting Hampden

AT109, which experienced a great deal of flak as it crossed the Norwegian

coast. He realised they were rapidly losing fuel. Rather than risk the engines

cutting out, he took the first opportunity to land. He touched down safely on a

strip of heather adjoining a beach near Vardo, in northern Norway. Jimmy, his

navigator Flying Officer George ‘Bob’ Anderson, wireless operator/upper gunner

Flight Sergeant Cecil Cameron, lower rear gunner Sergeant John Hayes and their

passenger Flight Sergeant John Davidson, a ground crew fitter, attempted to

destroy the Hampden, but they were fired on by soldiers from one direction and

a patrol boat from the coast. The five were taken prisoner; Bob Anderson and

Jimmy were sent to Stalag Luft III.

455 Squadron, April 1942. L-R Wilson, Bob Anderson, Smart, Humphrey, Acting S/L Jimmy Catanach DFC,

Miller, and Clarke. https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/SUK10124/

Jimmy’s handful of earlier letters to his parents had

been upbeat and emphasised his good spirits. His letter of 28 March 1943 was

more subdued. He told Bill as much of the truth as he could within the

constraints of censorship. He confessed his part in the events precipitating

capture: ‘my arrival in enemy territory was far from glorious. I force landed

as a result of fuel shortage caused by a sequence of misfortunes, mostly due to

my own foolishness and partly due to climate conditions and enemy action’.

Although the memory of it still ‘gets me down a bit’ he tried to push

recollections aside and conceded that ‘present circumstances are not so bad’.

Food, thanks to Red Cross parcels—when available—‘is quite good’ and living conditions

were tolerable, if ‘a bit trying’. By far ‘the worst thing’ was ‘the lack of

comradeship male & female and the futility of the existence.’ Even so, Jimmy

kept himself busy with exercise, cooking, study and reading. But even as he

made the most of life behind barbed wired, he planned for his future: ‘The end

of the war is the main interest and topic of conversation … I am going to try

studying Gem[m]ology & Bookkeeping etc. but am considering the idea of

staying in service’.

But, unlike the majority of Stalag Luft III’s

prisoners, Jimmy did not experience a life outside of captivity. Almost exactly

twelve months after writing to Bill, he was dead, one of fifty Allied

airmen—including five Australians—killed in the ‘Great Escape’ reprisals.

Jimmy after he had been captured after the mass breakout. Lifted from http://twicsy.com/i/6iideb

The men of Stalag Luft III were shocked, ‘shaken and

despondent’ when they heard of the death of their fellow prisoners. They held a

memorial parade after roll call. They wore black flashes. They observed a

period of mourning. They commemorated the dead in their wartime log books.

Later, they built a memorial to comrades who had merely been carrying out their

service duty to escape.

Sagan Memorial to the Fifty, courtesy of Geoff Swallow

Jimmy’s loss in particular affected his friends:

Ronnie Baines who he had welcomed and taken under his wing and into his room on

Baines’ first day in Stalag Luft III; Tony Gordon who had trained with him and

never stopped grieving for his first RAAF friend; Bob Anderson who had flown

with him and whose friendship had been forged under difficult and dangerous

conditions.

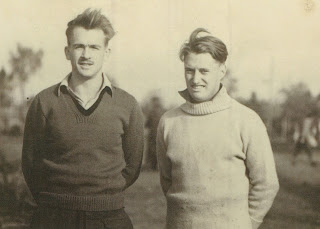

Ronnie Baines

Tony Gordon and Jimmy Catanach, courtesy of Drew Gordon

Bob Anderson. Courtesy of David Archer

On Anzac Day 1944—less than three weeks after they had

heard the ‘crushing news’ that most of those who had participated in the mass

breakout of 24/25 March had been killed on Hitler’s orders—Jimmy’s Australian

friends of North Compound gathered in the theatre with their compatriots from New

Zealand. There, Padre Watson took a special Anzac Day service. Afterwards, they

assembled for a series of group photographs taken by one of the German guards.

Anzac Day 1944. https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/P00270.027

The Australian ranks were depleted: as well as Jimmy,

Albert Hake, John Williams, Reg Kierath and Thomas Leigh had been executed. Dressed

as smartly as could be in worn RAAF and RAF uniforms, they proudly declared

that they were air force men. On the day in which Australians and New Zealanders,

honour their war dead, their photos were as much statements of Australian pride,

unity and defiance against the enemy as they were portraits of grief. Last

year, Jimmy had stood with them on Anzac Day.

Anzac Day 1943. Courtesy of Ian Fraser

This year he was missing, ‘his

duty fearlessly and nobly done’. But, he was ‘Ever remembered’.

Jimmy

Catanach’s headstone, Old Garrison Cemetery, Posen, courtesy of Geoff

Swallow,

Photographic

Archive of Headstones and Memorials WW2 by Spidge

Jimmy Catanach’s letters are held by the Shrine of Remembrance, Melbourne. I would like to thank Jenna Blyth, Collections Manager, and Neil Sharkey, Exhibitions Curator, who allowed me to consult the James Catanach Collection in October 2016.