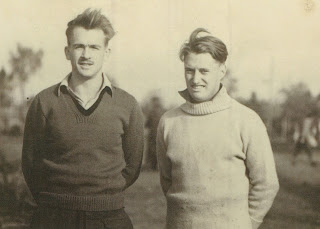

Charlie

Fry and Beryl Smith had known each other for five or six years when he embarked

for the UK in July 1937.

(Photo with application for Point Cook cadetship, NAA A9300, Fry, C.H.)

A graduate of 20 Course, 1 Flying Training School,

Point Cook (ranked 16th with 70.9 per cent) he was on his way to take up a short

service commission with the RAF. The couple wouldn’t see each other again for a

little over eight years.

(20 Course, 1 Flying Training School, Point Cook. Fry, front row, third from left. Courtesy RAAF Museum.)

After completing his training in the UK, and a brief

stint in 32 Squadron, Charlie joined 112 Squadron RAF, transferring to Egypt in

May 1939, flying Gladiators. The couple wrote regularly during their

separation, but after almost two years apart they missed each other terribly.

As war clouds thickened, Charlie had ‘had a bit of the blues for the last couple

of months’ but letters from Beryl—or Bebs—were just the tonic he needed to

cheer him up. Photos were also a significant means of maintaining their strong

connection and helped him imagine what she was doing back in Australia while he

was on operational service. ‘They were lovely snaps of you dear, and [I] would

very much like to have some others too if you have them, I can just imagine

what a lovely time you must be having’. They also kindled regret at the fun

times they were missing out on as a couple. ‘God I wish I were home.’

(Beryl Smith. Courtesy of the Fry family archive.)

Two months after the outbreak of war, Charlie wrote to

Beryl with the question he wished he had put to her before he left Australia.

He hadn’t, though, because ‘I sincerely wanted to ask you to wait for me to

return home, but I did not dare to, as it seemed so unfair because five

years’—the period of his short service commission—‘is a very long time’. After

three years separation, and with a new war, however, everything was different.

‘Please darling, this is a proposal: I want to marry you’. Moreover, he wanted

her to come to Egypt so they could be together.

(Unattributed engagement notice. Courtesy of the Fry family archive.)

Beryl

accepted immediately, but it was over a month before Charlie received word. He

was ecstatic: ‘At last my dream of almost eight years has materialised and I am

very proud and happy of what we have so far accomplished. I was out on a desert

landing ground when an aircraft brought your cable, and the pilot thought I had

gone crazy with the antics that I performed’.

Much

as they wanted to, it was not possible for Beryl to cross the world to be with

her new fiancé. Within months, 112 Squadron was in action. From Egypt it moved

to Greece, and then to Crete. Gladiators had been traded for Hurricanes and

Charlie, now a flight commander, was in frequent combat. ‘Crete was being

subjected to Stuka attacks and the sky was often thick with Messerschmitts’, he

later recalled. On 16 May 1941, ‘a fateful day’, Charlie, or Digger, as he was

known almost from the time he had set foot in England, was in battle yet again:

‘They appeared again in

the very early morning, followed by Ju88s, Dornier 17s, and Ju52s. Crete was

subjected to a great softening-up before the troop-carrying gliders came on the

scene. The sky also turned white with the canopies of German parachutists. The

tide of our war had turned.’

Charlie

was attacked: ‘My Hurricane lay in ruins after I was shot down, but I survived’.

Injured and unable to fly, Charlie made himself

useful. He set about building pens to protect the squadron’s aircraft. As Crete

fell to the Germans, and their aerodrome was taken, Charlie attempted to

construct another strip in the hills. When he realised there was no hope, he

organised the evacuation of the remaining squadron members. As one of his comrades

recollected, ‘He used to lay up in the hills during the day, and at night he

would take … [his men] down to the beaches on the off-chance of a warship being

around. I know there were occasions when he could have made his escape but he

preferred, as is the duty of an officer, to remain with his men to the

last—good old Digger’.

Charlie succeeded in getting off two officers and

three airmen before he was captured on 6 June 1941. He was the last of the

squadron’s officers remaining on Crete. And so, lauded his friend, ‘he remained

at his post to the last. A good pilot, a good officer, and an excellent leader

of men’. (His service in Greece was later acknowledged by a Greek DFC and a

British DFC.)

For

Beryl, who had regularly received letters from her fiancé, there was only worrying

silence and unanswered questions: what had happened to Charlie? And then, on 14

August, ‘It was with gladness and thanksgiving, after many weeks of knowing you

to be missing that I heard you were a Prisoner of War. Chas it is impossible to

describe how happy and relieved I was to learn of your whereabouts. I sincerely

hope you are well and safe’. Four days earlier, Charlie had written his first

missive to her since capture: ‘At last I am able to write to you I am very well

and uninjured’. It took over four months before those precious words arrived

just after Christmas 1941.

(POW identity card, Charles Horace Fry 40047, NAA A13950.)

(POW postcard, Charles Fry to Beryl Smith, 10 August 1941, received 29 December 1941.

Courtesy of the Fry family archive.)

Courtesy of the Fry family archive.)

In

that first POW postcard, Charlie wrote that he had lost all his photos of Beryl on

Crete and asked if she would send him some more. So treasured was her image—and

perhaps also conscious of the changes brought about by passing time—it was a

question he continued to ask throughout almost four years of captivity. Beryl

did not hesitate to respond. Indeed, throughout his captivity, she placed Charlie

and his needs firmly at the centre of her life.

She

joined the POW Relatives’ Association, she raised funds for the association,

assiduously read its newsletter, made contact with other families of captives,

spoke with a repatriated prisoner, all to glean information about Charlie and

the prisoner of war camps in which he was incarcerated. She diligently worked for

his comfort.

(Beryl Smith. Courtesy of the Fry family archive.)

She wrote frequently, sent photos, arranged for cigarette and book

parcels to be sent to him, contributed financially to parcels sent from British relatives, kept in

touch with his family and friends, lobbied for his actions to be appropriately

recognised, and sought future career advice on his behalf. She wrote about

family, a little about what she did in her limited spare time so he could

picture her life but, as a minister’s confidential typist, she could write

little of her career.

(Beryl Smith’s receipts from David Jones for parcels. Courtesy of the Fry family archive.)

(Letter from Beryl Smith to the Editor, The Sydney Morning Herald, 20 December 1943. Courtesy of the Fry family archive.)

Beryl

provided Charlie with a real link to home. He in turn did his best to maintain

that link. As well as his regular letters, he asked the Irving Air Chute

company to send Beryl the caterpillar pin which signified that ‘he had saved

his life with one our chutes’.

(Letter to Beryl Smith from the Caterpillar Club, 7 September 1943. Courtesy of the Fry family archive.)

(The Sunday Sun, 9 November 1943. Courtesy of the Fry family archive.)

Most

of Beryl’s letters—and Charlie’s to her—focused on their love for each other.

‘My love’; ‘my darling’; how much they ‘missed’ each other. Interestingly, they

wrote little of the future, or the life they planned to share with each other.

As Charlie’s captivity dragged on, the most important thing for each was to

reinforce the strength of their love.

During the course of his long captivity, Charlie spent

time in Oflag XC, Lubeck, Oflag VIB, Warburg, Stalag Luft III, and Oflag XXIB,

Schubin. On 2 April 1943, he returned to Stalag Luft III. Captivity was not an easy state for Charlie. He endured physical and psychological stresses but he appeared to suffer more from his long separation from Beryl. She too felt the strain of being apart. They tried to be cheerful, but both had doubts about the

other’s constancy, and they did little to hide it.

‘Charl,

dearest, I love you very very much—it is most anguishing to be separated from

you for so long and I am looking forward longingly to the day when I shall be

in your arms again. You are the only one I care for (or have ever cared for

Chas)—since the very first day I met you … . I sincerely hope, Chas, that you

reciprocate my feelings and that these long years apart have not dimmed your

ardour for me.’

Both

were conscious of the passage of years. On 29 November 1943, Charles wrote, ‘By

the time this will reach you, you will have had your 28th birthday. [Beryl was

born on 5 March 1915.] Happy returns darling gosh I wish I were here with you

darling for I would have lots more to tell you. I miss you darling and hope we

shall be together again soon. Cheerio my dear you have all my love, yours for

ever’.

(Charles Fry in Oflag XXIB, Schubin late 1942, after their heads were shaven. Fry second from left.

Courtesy of the Fry family archive.)

By

December 1944, the strain was almost unendurable. It was their seventh

Christmas apart and Charlie’s fourth in captivity. He had sent her Christmas

cards in times past but if he had this time, it did not reach her.

(Christmas Card from No 1 Flying Training School, RAAF Point Cook, 1936. Courtesy of the Fry family archive.)

(POW Christmas card from Charles Fry to Beryl Smith POW, postmarked 22 November 1942 while he was in Schubin, received 12 March 1942. Courtesy of the Fry family archive.)

On 12

December, Beryl wrote again to Charles. It was her last letter addressed to him

at Stalag Luft III, yet he never received it. [She typed all of her letters and

kept the flimsy.] ‘How are you, my precious darling? Sick and tired of waiting,

I guess. I feel that way at times too. Not tired of waiting for you my darling

but tired of having to wait.’ It was a poignant letter, full of all the longing

a woman felt for a man she had not seen since July 1937. It suggested a silence

that, despite the many letters over the years, stretched between them. It

hinted at the things that could not be told because of censorship, or because

they both recognised that ‘one must keep a happy exterior and write bright

cheery letters’, or because some words simply could not be put on paper: they

could only be whispered between lovers entwined in each other’s arms:

‘I

wish I could express what is in my mind—tell you how I feel and what thoughts I

have about life, the war and ourselves … . I really think of some marvellous

things to say to you but when I come to write them it is very very difficult. I

feel I would like to tell you how much I love you and adore you and that you

are the embodiment of all my dreams—that I miss you very very much and am often

unhappy and sad about that. I would like to tell you that I dream of the time

we will be together and that you will say that you love me and think that I am

beautiful … I try to imagine what it will be like to have your arms around me

and to feel your kisses.’

As

Beryl wondered what she would do when they were reunited—‘Will I rush forward

and throw my arms madly around your neck and kiss you and kiss you and kiss

you—or will I stand shyly by whilst you embrace your mother and family and wait

my turn later on’—Charlie was having a ‘miserable Christmas’. ‘How I would like

to be with you there’, he wrote. He had been at a low ebb during the last weeks

of 1944 as the hoped-for release in the wake of the D-Day invasion had failed

to eventuate. The only joy was the ‘lovely Christmass [sic] present of three

letters … Thanks darling they were lovely letters’. Realising yet another

birthday was nigh, he wrote, ‘Hope you receive this before your birthday

darling with all my love for a happy birthday & may the next one be happier’.

Beryl’s

30th birthday was no happier. Charlie still had not returned to her and, by

March 1945, was off the radar. She had not heard from him for weeks. Mail from

Germany was irregular at that stage of the war and Charlie had not written

since the prisoners had evacuated from Stalag Luft III at the end of January

1945. After months of silence and anxiety over Charlie’s fate, Beryl finally

heard the wonderful news that he had been liberated and was back in England. ‘There

are no words to express my happiness and joy’, she wrote on 14 May. ‘Oh my

darling. I am so happy. I sincerely trust you are in good health and none the

worse for your experiences. Gee Charles it is hard to believe after all these

years. I can hardly wait to see you, dearest, and to have your arms around me.’

(August 1945, taken at Buckingham Palace just after DFC investiture. Unknown source.)

Charlie

was soon on his way, excited to be returning home and to Beryl. On 6 September

1945, as he approached Australian waters six years to the day when he had

proposed by letter, he sent the most welcome telegram: ‘Be with you soon for good.

Happy excited love Charles’.

(Courtesy of the Fry family archive.)

Charlie disembarked in Sydney on the 9th. Less

than two weeks later, on 22 September 1945, Charlie and Beryl married. They

were together at last: ‘for good’.

(Cutting the cake. 22 September 1945. Courtesy of the Fry family archive.)